As legitimate media outlets have reported, there are many fake TikTok videos about the war in Ukraine. Investigators found that some of these videos use sound taken from video games. Of course, there are MANY real videos on TikTok too. Either way, TikTok is dominating the online conversation. In the New York Times this week, the reporter Sheera Frenkel writes:

“The volume of war content on the app far outweighs what is found on some other social networks, according to a review by The Times. Videos with the hashtag #Ukrainewar have amassed nearly 500 million views on TikTok, with some of the most popular videos gaining close to one million likes. In contrast, the #Ukrainewar hashtag on Instagram had 125,000 posts and the most popular videos were viewed tens of thousands of times.”

What to do about the fake videos on TikTok? The answers are not easy.

“Video is the hardest format to moderate for all platforms,” said Alex Stamos, the director of the Stanford Internet Observatory and a former head of security at Facebook. TikTok serves up video based on an algorithm primarily; friendships and follows don’t matter as much. “This makes TikTok a uniquely potent platform for viral propaganda,” Stamos says.

TikTok is uniquely set up for creators to post-war videos because, as Chris Stokel-Walker writes this week in Wired:

“Its in-app editing and filters make it easier than any other platform to capture and share the world around us. If Facebook is bloated, Instagram is curated, and YouTube requires a shedload of equipment and editing time, TikTok is quick and dirty — the kind of video platform that can shape perceptions of how a conflict is unfolding.”

Youth already are facing so many stressors, and now this new anxiety-producing reality is playing out in social feeds 24/7. This is the first time they’ve seen war in this capacity for many young people. In The New York Times article referenced earlier, a 19-year-old girl says she’s spending hours watching TikTok videos of footage from the war.

“What I see on TikTok is more real, more authentic than other social media,” said Bre Hernandez, a student in Los Angeles. “I feel like I see what people there are seeing.”

Stokel-Walker says in Wired, “Prior research has shown that fake news travels six times faster than legitimate information on social media – in large part because of its ability to trigger a strong emotional response.”

Meanwhile, we know from studies that when youth struggle emotionally, they are more susceptible to being triggered by the news. In one nationally representative survey by researchers Rideout and Fox of 14 to 22 year-olds in the U.S., those who were experiencing depression symptoms were four times more likely to answer the following question affirmatively:

“When I see so much bad news, I feel stressed or anxious.”

Learn more about showing our movies in your school or community!

Join Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD for our latest Podcast

Learn more about our Screen-Free Sleep campaign at the website!

Our movie made for parents and educators of younger kids

Learn more about showing our movies in your school or community!

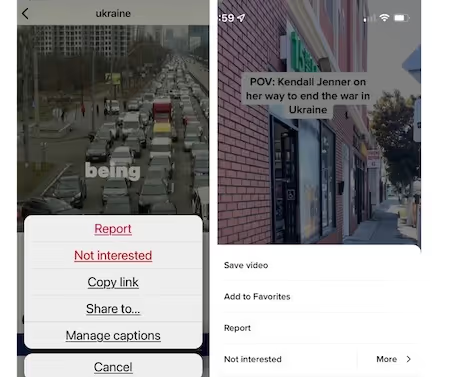

it is important to understand this and reach out to our kids right now to help them with strategies to handle this barrage of disturbing content. My film partner, Lisa, said her 18-year-old daughter had been upset by all the war content she sees on her social feeds. She says that she will quickly scroll past the war videos and, eventually, her feeds learn that she doesn’t want to watch them and stops serving them up so much. Her daughter wants to learn about what is going on and instead will listen to a podcast like The New York Times’ “The Daily” to dive deeper. She also told Lisa that Instagram lets you flag content you don’t want to see by doing this:

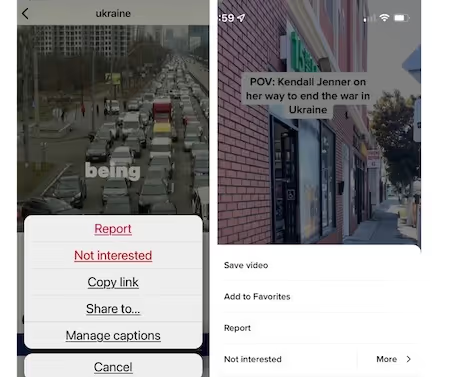

A similar setting in TikTok:

Just “Long-press” videos you don't like and tap the "Not interested" icon that pops up to see less of it in the future.

David Fassler, M.D. is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and has written 15 tips for Talk To Kids About The War In Ukraine for the AACAP (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry), here are a few of his tips:

1. “Give children honest answers and information. Children will usually know, or eventually find out if you’re “making things up.” It may affect their ability to trust you or your reassurances in the future.”

2. “Be prepared to repeat information and explanations several times. Some information may be hard to accept or understand. Asking the same question over and over may also be a way for a child to ask for reassurance.”

3. “Let children know how you’re feeling. It’s OK for children to know if you are anxious or worried about world events. Children will usually pick it up anyway, and if they don’t know the cause, they may think it’s their fault. They may worry that they’ve done something wrong.”

As parents, it’s important we make sure our kids know that some of what they see might not be real.

Teaching our kids to be good fact-checkers is one way we can help. I wrote about this in a preview Screenagers’ Tech Tuesday titled, How To Think Like A Fact Checker. (Also, listen to the episode of our Screenagers Podcast director of the Stanford History Education Group who has analyzed how college students, historians, and fact-checkers evaluate websites to create effective strategies for spotting disinformation.) Here’s a passage from the blog:

Learn more about showing our movies in your school or community!

Join Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD for our latest Podcast

Learn more about our Screen-Free Sleep campaign at the website!

Our movie made for parents and educators of younger kids

Join Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD for our latest Podcast

Three big questions guiding fact-checkers as they evaluate online sources are 1. Who's behind this information, and what’s their evidence? 2. What’s the evidence, or is there even evidence presented? 3. What are other sources saying? So as not to rely on a single source, look for multiple sources, and do they say something similar?

1. Do you ever use the “not interested” options on videos you see in your social feeds? If so, do you notice then similar content stops appearing as much?

2. Are you seeing many videos of the war in Ukraine on your feeds? Do you watch them? Do you know that some could be fake, and some even use sound from video games on them?

3. How does it make you feel when you see these videos? Do you have strategies to help yourself from stopping?

As we’re about to celebrate 10 years of Screenagers, we want to hear what’s been most helpful and what you’d like to see next.

Please click here to share your thoughts with us in our community survey. It only takes 5–10 minutes, and everyone who completes it will be entered to win one of five $50 Amazon vouchers.

As legitimate media outlets have reported, there are many fake TikTok videos about the war in Ukraine. Investigators found that some of these videos use sound taken from video games. Of course, there are MANY real videos on TikTok too. Either way, TikTok is dominating the online conversation. In the New York Times this week, the reporter Sheera Frenkel writes:

“The volume of war content on the app far outweighs what is found on some other social networks, according to a review by The Times. Videos with the hashtag #Ukrainewar have amassed nearly 500 million views on TikTok, with some of the most popular videos gaining close to one million likes. In contrast, the #Ukrainewar hashtag on Instagram had 125,000 posts and the most popular videos were viewed tens of thousands of times.”

What to do about the fake videos on TikTok? The answers are not easy.

“Video is the hardest format to moderate for all platforms,” said Alex Stamos, the director of the Stanford Internet Observatory and a former head of security at Facebook. TikTok serves up video based on an algorithm primarily; friendships and follows don’t matter as much. “This makes TikTok a uniquely potent platform for viral propaganda,” Stamos says.

TikTok is uniquely set up for creators to post-war videos because, as Chris Stokel-Walker writes this week in Wired:

“Its in-app editing and filters make it easier than any other platform to capture and share the world around us. If Facebook is bloated, Instagram is curated, and YouTube requires a shedload of equipment and editing time, TikTok is quick and dirty — the kind of video platform that can shape perceptions of how a conflict is unfolding.”

Youth already are facing so many stressors, and now this new anxiety-producing reality is playing out in social feeds 24/7. This is the first time they’ve seen war in this capacity for many young people. In The New York Times article referenced earlier, a 19-year-old girl says she’s spending hours watching TikTok videos of footage from the war.

“What I see on TikTok is more real, more authentic than other social media,” said Bre Hernandez, a student in Los Angeles. “I feel like I see what people there are seeing.”

Stokel-Walker says in Wired, “Prior research has shown that fake news travels six times faster than legitimate information on social media – in large part because of its ability to trigger a strong emotional response.”

Meanwhile, we know from studies that when youth struggle emotionally, they are more susceptible to being triggered by the news. In one nationally representative survey by researchers Rideout and Fox of 14 to 22 year-olds in the U.S., those who were experiencing depression symptoms were four times more likely to answer the following question affirmatively:

“When I see so much bad news, I feel stressed or anxious.”

it is important to understand this and reach out to our kids right now to help them with strategies to handle this barrage of disturbing content. My film partner, Lisa, said her 18-year-old daughter had been upset by all the war content she sees on her social feeds. She says that she will quickly scroll past the war videos and, eventually, her feeds learn that she doesn’t want to watch them and stops serving them up so much. Her daughter wants to learn about what is going on and instead will listen to a podcast like The New York Times’ “The Daily” to dive deeper. She also told Lisa that Instagram lets you flag content you don’t want to see by doing this:

A similar setting in TikTok:

Just “Long-press” videos you don't like and tap the "Not interested" icon that pops up to see less of it in the future.

David Fassler, M.D. is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and has written 15 tips for Talk To Kids About The War In Ukraine for the AACAP (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry), here are a few of his tips:

1. “Give children honest answers and information. Children will usually know, or eventually find out if you’re “making things up.” It may affect their ability to trust you or your reassurances in the future.”

2. “Be prepared to repeat information and explanations several times. Some information may be hard to accept or understand. Asking the same question over and over may also be a way for a child to ask for reassurance.”

3. “Let children know how you’re feeling. It’s OK for children to know if you are anxious or worried about world events. Children will usually pick it up anyway, and if they don’t know the cause, they may think it’s their fault. They may worry that they’ve done something wrong.”

As parents, it’s important we make sure our kids know that some of what they see might not be real.

Teaching our kids to be good fact-checkers is one way we can help. I wrote about this in a preview Screenagers’ Tech Tuesday titled, How To Think Like A Fact Checker. (Also, listen to the episode of our Screenagers Podcast director of the Stanford History Education Group who has analyzed how college students, historians, and fact-checkers evaluate websites to create effective strategies for spotting disinformation.) Here’s a passage from the blog:

Three big questions guiding fact-checkers as they evaluate online sources are 1. Who's behind this information, and what’s their evidence? 2. What’s the evidence, or is there even evidence presented? 3. What are other sources saying? So as not to rely on a single source, look for multiple sources, and do they say something similar?

1. Do you ever use the “not interested” options on videos you see in your social feeds? If so, do you notice then similar content stops appearing as much?

2. Are you seeing many videos of the war in Ukraine on your feeds? Do you watch them? Do you know that some could be fake, and some even use sound from video games on them?

3. How does it make you feel when you see these videos? Do you have strategies to help yourself from stopping?

Sign up here to receive the weekly Tech Talk Tuesdays newsletter from Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD.

We respect your privacy.

As legitimate media outlets have reported, there are many fake TikTok videos about the war in Ukraine. Investigators found that some of these videos use sound taken from video games. Of course, there are MANY real videos on TikTok too. Either way, TikTok is dominating the online conversation. In the New York Times this week, the reporter Sheera Frenkel writes:

“The volume of war content on the app far outweighs what is found on some other social networks, according to a review by The Times. Videos with the hashtag #Ukrainewar have amassed nearly 500 million views on TikTok, with some of the most popular videos gaining close to one million likes. In contrast, the #Ukrainewar hashtag on Instagram had 125,000 posts and the most popular videos were viewed tens of thousands of times.”

What to do about the fake videos on TikTok? The answers are not easy.

“Video is the hardest format to moderate for all platforms,” said Alex Stamos, the director of the Stanford Internet Observatory and a former head of security at Facebook. TikTok serves up video based on an algorithm primarily; friendships and follows don’t matter as much. “This makes TikTok a uniquely potent platform for viral propaganda,” Stamos says.

TikTok is uniquely set up for creators to post-war videos because, as Chris Stokel-Walker writes this week in Wired:

“Its in-app editing and filters make it easier than any other platform to capture and share the world around us. If Facebook is bloated, Instagram is curated, and YouTube requires a shedload of equipment and editing time, TikTok is quick and dirty — the kind of video platform that can shape perceptions of how a conflict is unfolding.”

Youth already are facing so many stressors, and now this new anxiety-producing reality is playing out in social feeds 24/7. This is the first time they’ve seen war in this capacity for many young people. In The New York Times article referenced earlier, a 19-year-old girl says she’s spending hours watching TikTok videos of footage from the war.

“What I see on TikTok is more real, more authentic than other social media,” said Bre Hernandez, a student in Los Angeles. “I feel like I see what people there are seeing.”

Stokel-Walker says in Wired, “Prior research has shown that fake news travels six times faster than legitimate information on social media – in large part because of its ability to trigger a strong emotional response.”

Meanwhile, we know from studies that when youth struggle emotionally, they are more susceptible to being triggered by the news. In one nationally representative survey by researchers Rideout and Fox of 14 to 22 year-olds in the U.S., those who were experiencing depression symptoms were four times more likely to answer the following question affirmatively:

“When I see so much bad news, I feel stressed or anxious.”

It feels like we’re finally hitting a tipping point. The harms from social media in young people’s lives have been building for far too long, and bold solutions can’t wait any longer. That’s why what just happened in Australia is extremely exciting. Their new nationwide move marks one of the biggest attempts yet to protect kids online. And as we released a new podcast episode yesterday featuring a mother who lost her 14-year-old son after a tragic connection made through social media, I couldn’t help but think: this is exactly the kind of real-world action families have been desperate for. In today’s blog, I share five key things to understand about what Australia is doing because it’s big, it’s controversial, and it might just spark global change.

READ MORE >

I hear from so many parents who feel conflicted about their own phone habits when it comes to modeling healthy use for their kids. They’ll say, “I tell my kids to get off their screens, but then I’m on mine all the time.” Today I introduce two moms who are taking on my One Small Change Challenge and share how you can try it too.

READ MORE >

This week’s blog explores how influencers and social media promoting so-called “Healthy” ideals — from food rules to fitness fads — can quietly lead young people toward disordered eating. Featuring insights from Dr. Jennifer Gaudiani, a leading expert on eating disorders, we unpack how to spot harmful messages and start honest conversations with kids about wellness, body image, and what “healthy” really means.

READ MORE >for more like this, DR. DELANEY RUSTON'S NEW BOOK, PARENTING IN THE SCREEN AGE, IS THE DEFINITIVE GUIDE FOR TODAY’S PARENTS. WITH INSIGHTS ON SCREEN TIME FROM RESEARCHERS, INPUT FROM KIDS & TEENS, THIS BOOK IS PACKED WITH SOLUTIONS FOR HOW TO START AND SUSTAIN PRODUCTIVE FAMILY TALKS ABOUT TECHNOLOGY AND IT’S IMPACT ON OUR MENTAL WELLBEING.