I confess I have taken down a few posts on my personal Facebook page in the past because they didn’t get any comments or “Likes.” I find it a little embarrassing to admit that. Yet that said, feelings like embarrassment and other uncomfortable emotions help me decide what I want to blog about. I believe our emotions speak to our shared universal truths.

When I didn’t get interactions on a post, a wave of different feelings went through my head: anger — does the algorithm not show this to others? Insecurity — is my post so irrelevant to people that they don’t care about it and don’t care about me?

Of course, my logical brain would immediately step in and say, “No, no Delaney, all good, just keep the post there. Some folks probably saw it and could have helped people. Just relax.” The emotional side of my brain said, “Well, hun, you feel bad, it’s ok, you can take it down.” And on a few occasions over the years, the emotional side of my brain won out. I hit the “delete post” button.

Today I’m writing about what the Wall Street Journal’s reporting on the Facebook Files tells us about what Facebook and Instagram know about “Likes” and what they are not telling us, and solutions on how we can help our youth with “Likes.”

I have been particularly frustrated with Facebook and Instagram in the handling of their experiments in getting rid of “Likes” for some users as part of a test. I distinctly remember being with my family at Thanksgiving in 2019 when a 28-year old family member said, “Hey, look, my “Likes” are gone!” This prompted folks to look at their Instagram accounts, and we learned he was the only one whose “Likes” were gone.

Around that time, Instagram and Facebook started saying how they were doing experiments around “Likes,” but they were sharing very little information. For example, I could not find out whether they used a random process to determine who they hid “Likes” from.

Over the years since that time, I haven’t been able to find information on their experiment’s findings.

Now cut to the present and the leaking of documents by Frances Haugen to the Wall Street Journal. In one of the articles by the reporter, Jeff Horwitz, he wrote the following:

“Teens told Facebook in focus groups that “like” counts caused them anxiety and contributed to their negative feelings.

When Facebook tested a tweak to hide the “likes” in a pilot program they called Project Daisy, it found it didn’t improve life for teens. “We didn’t observe movements in overall well-being measures,” Facebook employees wrote in a slide they presented to Mr. Zuckerberg about the experiment in 2020.

So my question to Facebook and Instagram is, “Where is the data?! What are the numbers? What percentage of teens said that it didn’t improve their life?”

It all feels very secretive to me.

Learn more about showing our movies in your school or community!

Join Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD for our latest Podcast

Learn more about our Screen-Free Sleep campaign at the website!

Our movie made for parents and educators of younger kids

Learn more about showing our movies in your school or community!

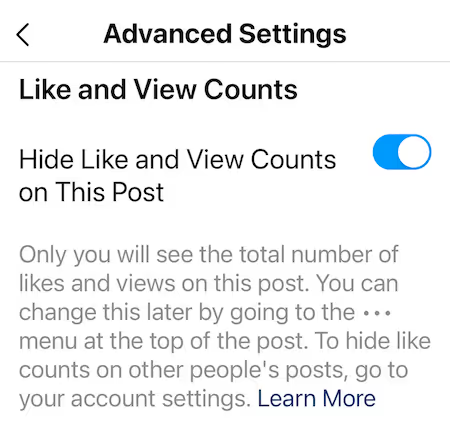

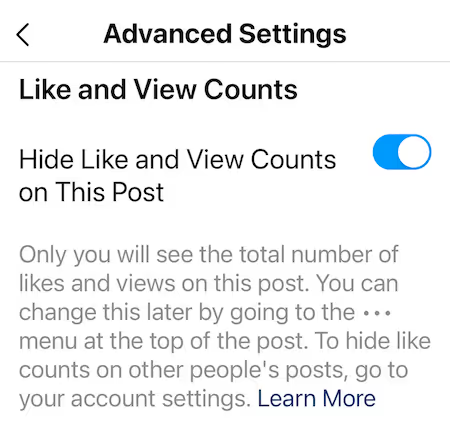

This past May, Facebook and Instagram decided to make an option that allows all users to hide the outward-facing numbers of “Likes.” You, the user, however, can still see the “Likes.”

On the Instagram app:

Turning off “Likes” on Facebook is not quite as easy as doing it on Instagram:

In that same article, Horwitz wrote this that does not put a good light on Facebook:

“...Facebook rolled out the change as an option for Facebook and Instagram users in May 2021 after senior executives argued to Mr. Zuckerberg that it could make them look good by appearing to address the issue, according to the documents. ‘A Daisy launch would be received by press and parents as a strong positive indication that Instagram cares about its users, especially when taken alongside other press-positive launches,’ Facebook executives wrote in a discussion about how to present their findings to Mr. Zuckerberg?”

Learn more about showing our movies in your school or community!

Join Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD for our latest Podcast

Learn more about our Screen-Free Sleep campaign at the website!

Our movie made for parents and educators of younger kids

Join Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD for our latest Podcast

Solutions

So what are some of the things we can do related to all the many issues around “Likes” that any social media user faces, both adults and youth?

As we’re about to celebrate 10 years of Screenagers, we want to hear what’s been most helpful and what you’d like to see next.

Please click here to share your thoughts with us in our community survey. It only takes 5–10 minutes, and everyone who completes it will be entered to win one of five $50 Amazon vouchers.

I confess I have taken down a few posts on my personal Facebook page in the past because they didn’t get any comments or “Likes.” I find it a little embarrassing to admit that. Yet that said, feelings like embarrassment and other uncomfortable emotions help me decide what I want to blog about. I believe our emotions speak to our shared universal truths.

When I didn’t get interactions on a post, a wave of different feelings went through my head: anger — does the algorithm not show this to others? Insecurity — is my post so irrelevant to people that they don’t care about it and don’t care about me?

Of course, my logical brain would immediately step in and say, “No, no Delaney, all good, just keep the post there. Some folks probably saw it and could have helped people. Just relax.” The emotional side of my brain said, “Well, hun, you feel bad, it’s ok, you can take it down.” And on a few occasions over the years, the emotional side of my brain won out. I hit the “delete post” button.

Today I’m writing about what the Wall Street Journal’s reporting on the Facebook Files tells us about what Facebook and Instagram know about “Likes” and what they are not telling us, and solutions on how we can help our youth with “Likes.”

I have been particularly frustrated with Facebook and Instagram in the handling of their experiments in getting rid of “Likes” for some users as part of a test. I distinctly remember being with my family at Thanksgiving in 2019 when a 28-year old family member said, “Hey, look, my “Likes” are gone!” This prompted folks to look at their Instagram accounts, and we learned he was the only one whose “Likes” were gone.

Around that time, Instagram and Facebook started saying how they were doing experiments around “Likes,” but they were sharing very little information. For example, I could not find out whether they used a random process to determine who they hid “Likes” from.

Over the years since that time, I haven’t been able to find information on their experiment’s findings.

Now cut to the present and the leaking of documents by Frances Haugen to the Wall Street Journal. In one of the articles by the reporter, Jeff Horwitz, he wrote the following:

“Teens told Facebook in focus groups that “like” counts caused them anxiety and contributed to their negative feelings.

When Facebook tested a tweak to hide the “likes” in a pilot program they called Project Daisy, it found it didn’t improve life for teens. “We didn’t observe movements in overall well-being measures,” Facebook employees wrote in a slide they presented to Mr. Zuckerberg about the experiment in 2020.

So my question to Facebook and Instagram is, “Where is the data?! What are the numbers? What percentage of teens said that it didn’t improve their life?”

It all feels very secretive to me.

This past May, Facebook and Instagram decided to make an option that allows all users to hide the outward-facing numbers of “Likes.” You, the user, however, can still see the “Likes.”

On the Instagram app:

Turning off “Likes” on Facebook is not quite as easy as doing it on Instagram:

In that same article, Horwitz wrote this that does not put a good light on Facebook:

“...Facebook rolled out the change as an option for Facebook and Instagram users in May 2021 after senior executives argued to Mr. Zuckerberg that it could make them look good by appearing to address the issue, according to the documents. ‘A Daisy launch would be received by press and parents as a strong positive indication that Instagram cares about its users, especially when taken alongside other press-positive launches,’ Facebook executives wrote in a discussion about how to present their findings to Mr. Zuckerberg?”

Solutions

So what are some of the things we can do related to all the many issues around “Likes” that any social media user faces, both adults and youth?

Sign up here to receive the weekly Tech Talk Tuesdays newsletter from Screenagers filmmaker Delaney Ruston MD.

We respect your privacy.

I confess I have taken down a few posts on my personal Facebook page in the past because they didn’t get any comments or “Likes.” I find it a little embarrassing to admit that. Yet that said, feelings like embarrassment and other uncomfortable emotions help me decide what I want to blog about. I believe our emotions speak to our shared universal truths.

When I didn’t get interactions on a post, a wave of different feelings went through my head: anger — does the algorithm not show this to others? Insecurity — is my post so irrelevant to people that they don’t care about it and don’t care about me?

Of course, my logical brain would immediately step in and say, “No, no Delaney, all good, just keep the post there. Some folks probably saw it and could have helped people. Just relax.” The emotional side of my brain said, “Well, hun, you feel bad, it’s ok, you can take it down.” And on a few occasions over the years, the emotional side of my brain won out. I hit the “delete post” button.

Today I’m writing about what the Wall Street Journal’s reporting on the Facebook Files tells us about what Facebook and Instagram know about “Likes” and what they are not telling us, and solutions on how we can help our youth with “Likes.”

I have been particularly frustrated with Facebook and Instagram in the handling of their experiments in getting rid of “Likes” for some users as part of a test. I distinctly remember being with my family at Thanksgiving in 2019 when a 28-year old family member said, “Hey, look, my “Likes” are gone!” This prompted folks to look at their Instagram accounts, and we learned he was the only one whose “Likes” were gone.

Around that time, Instagram and Facebook started saying how they were doing experiments around “Likes,” but they were sharing very little information. For example, I could not find out whether they used a random process to determine who they hid “Likes” from.

Over the years since that time, I haven’t been able to find information on their experiment’s findings.

Now cut to the present and the leaking of documents by Frances Haugen to the Wall Street Journal. In one of the articles by the reporter, Jeff Horwitz, he wrote the following:

“Teens told Facebook in focus groups that “like” counts caused them anxiety and contributed to their negative feelings.

When Facebook tested a tweak to hide the “likes” in a pilot program they called Project Daisy, it found it didn’t improve life for teens. “We didn’t observe movements in overall well-being measures,” Facebook employees wrote in a slide they presented to Mr. Zuckerberg about the experiment in 2020.

So my question to Facebook and Instagram is, “Where is the data?! What are the numbers? What percentage of teens said that it didn’t improve their life?”

It all feels very secretive to me.

It feels like we’re finally hitting a tipping point. The harms from social media in young people’s lives have been building for far too long, and bold solutions can’t wait any longer. That’s why what just happened in Australia is extremely exciting. Their new nationwide move marks one of the biggest attempts yet to protect kids online. And as we released a new podcast episode yesterday featuring a mother who lost her 14-year-old son after a tragic connection made through social media, I couldn’t help but think: this is exactly the kind of real-world action families have been desperate for. In today’s blog, I share five key things to understand about what Australia is doing because it’s big, it’s controversial, and it might just spark global change.

READ MORE >

I hear from so many parents who feel conflicted about their own phone habits when it comes to modeling healthy use for their kids. They’ll say, “I tell my kids to get off their screens, but then I’m on mine all the time.” Today I introduce two moms who are taking on my One Small Change Challenge and share how you can try it too.

READ MORE >

This week’s blog explores how influencers and social media promoting so-called “Healthy” ideals — from food rules to fitness fads — can quietly lead young people toward disordered eating. Featuring insights from Dr. Jennifer Gaudiani, a leading expert on eating disorders, we unpack how to spot harmful messages and start honest conversations with kids about wellness, body image, and what “healthy” really means.

READ MORE >for more like this, DR. DELANEY RUSTON'S NEW BOOK, PARENTING IN THE SCREEN AGE, IS THE DEFINITIVE GUIDE FOR TODAY’S PARENTS. WITH INSIGHTS ON SCREEN TIME FROM RESEARCHERS, INPUT FROM KIDS & TEENS, THIS BOOK IS PACKED WITH SOLUTIONS FOR HOW TO START AND SUSTAIN PRODUCTIVE FAMILY TALKS ABOUT TECHNOLOGY AND IT’S IMPACT ON OUR MENTAL WELLBEING.